|

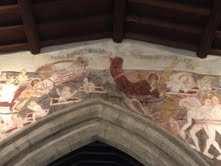

The LMS National Chaplain, Fr Southwell, distributing

Communion at the LMS Annual Mass in Southwark Cathedral. |

Suppose a person previously unknown to a priest pops into the sacristy just before Mass starts and announces to the priest: 'By the way, Father, I am in a objective state of mortal sin'. We may imagine this information is conveyed by a statement such as (out of wedlock) 'This is my lover'. Then, when it is time for Communion, this person is present in the line. Should the priest give the sinner Communion?

It is essentially this situation which the canonist Edward Peters deals with in his latest

blog post. Never mind any possibility of disputed facts, this is what Peters addresses, as a matter of principle. I appreciate a nice argument, and Peter's post is, in its own way, a thing of beauty. His answer is that there are no grounds for refusing Communion.

A priest should refuse Communion to a baptised Catholic on one of two grounds: 'notorious' public sin (canon 915), or objective lack of the right dispositions (canon 843). Although the person at issue has made her manner of life known to the priest, it is not clearly 'notorious' (known to the rest of the congregation), nor is it a matter of objective legal status (such as being divorced and remarried). And although she is clearly not properly disposed, her lack of right disposition does not count as objective (it's not what she's actually doing that day in public, it was a private statement to the priest), and subjective lack of disposition is something of which a priest cannot know.

Peters is getting a lot of flack for this position, and I should say that he is in general a Good Thing. He constantly reminds his readers of the reality of canon 915, and how it ought to exclude pro-abortion politicians and the like from Communion. He's no liberal. But the above argument seems to me a good example of the legalism into which many conservative Catholics have retreated. Peters has more excuse than most, because he is a canon lawyer, but it is a more widespread phenomenon. Because liberal dissidents are constantly getting away with defying Church law, Church law seems a good stick to beat them with, but the danger is that the law can be made into a fetish. We had this over the liceity of the 1962 Missal: for years we were told that 'most canonists' held the view that it had been abrogated. Well, it seems 'most canonists' were wrong, and now the Holy Father has said so. But for the period from 1969 to 2007 trads who made the argument that the 1962 books were still part of the Church's legitimate and current liturgical tradition were branded by conservatives as antinomians.

The fact is that common sense does have a part to play in the interpretation of law, in the Natural Law tradition, of which the Church's law is firmly a part. Natural justice, the good of souls, tradition, and moral and theological principles are in no way irrelevant to what is objectively and legally the right thing to do. I don't say Peters denies this. But in seeking a solution by the minute examination of the canons, and the words of their interpreters, as we would expect a canonist to do, he has come up with an answer which defies reason.

I am not a canonist, and I am willing to bow to the judgement of the Church on this, but let me just summarise what seems a bit barmy about Peters' conclusions.

1. Notoriety. Peters says the priest doesn't have sufficient grounds for assuming notoriety. But here is a woman who makes a point of telling him that she is in an immoral relationship. It is highly likely that (a) she is referring to co-habitation, which is a public matter, (b) her situation is known to a proportion of the congregation, who in this case are friends and relations of her late mother, and (c) she is telling everyone she meets who doesn't know about it, just as she is telling the priest. She is clearly 'out and proud', and wants people to know. By all means let us err on the side of caution when barring notorious sinners from Communion, but Peters' understanding of 'notoriety' seems to use the letter of the law (or of the tradition of its interpretation) to defeat its spirit. The law is to protect against public scandal, and it is public scandal which this lady wishes to cause by announcing her sinful way of life and then presenting herself for Communion.

2. Disposition. Priests can only bar people from Communion on the basis of what they, the priests, know - obviously - so the tradition of interpretation (Peters tells us) distinguishes between objective factors, knowable to the priest, and subjective ones, which are unknowable. Objective factors are understood by canonists as public ones, such as being evidently drunk. Subjective factors are the individual's state of sin or grace, which is in principle known only to God. But here we have the individual making known to the priest not only her sinful life but her being unrepentant, as far as it is possible to tell, so what is normally on the subjective side of the distinction is objectively verified as much as one could wish. If a priest can refuse Communion to someone he perceives as drunk, or who 'curses the minister', it is simply bizarre to suggest that because a sinful life at home would normally come under the 'subjective' heading it cannot cross the line into the objective category when the person at issue actually tells the priest about it. Again, the letter of (the interpretation of) the law appears to be defeating its spirit. The purpose of the law is to prevent sacrilegious Communions where the danger is so evident that there is no question of a Catholic being refused Communion unfairly. And that is exactly what is at issue here.

I would add two further points. In the world we live in, in the context of the debate going on about homosexuality and the Church, a priest with any psychological insight is perfectly justified in seeing the announcement of having a 'lover' as a deliberately provocative claim designed to lay a trap at Communion time. The fact that it was made impossible for the priest to continue the conversation any further strengthens this impression. The 'lovers' wished to make sure the priest knew that he was giving Communion to someone committed to an immoral way of life, so either they could show the world that the Church in practice will go along with such a way of life, or they could cry blue murder if the priest refused.

Now perhaps I'm assuming too much; I wasn't there. But - and this is the second point - this particular priest was there. He heard the tone of voice, he saw the body language. If he's going to be hung out to dry because what was perfectly clear to him doesn't tick certain boxes in the definition of public knowledge or objective bad disposition, then that is not only unjust but it creates a situation in which priests are going to be treated with a hermeneutic of suspicion which is simply unworkable. We have to allow priests, in awkward situations, where there is little time to consider all the tomes in Edward Peters' library, to take a reasonable view of a situation, and we even have to accept that they will make the occasional mistake. Regardless of what the canonists of old might have said, I find it hard to imagine priests getting in trouble for acting in this way in the days, sadly long gone, when there was some sanity applied to the government of the Church.

Let us pray for our priests this Lent.