Such was my excitement at receiving a letter from Mgr Loftus last week that I've missed the chance to fisk one of his articles. I don't want to miss another, so here are some comments on his latest, in which he wades into the 'fetid air of the swamp' of the debate about what Pope Benedict XVI said, or did not say, or meant, or did not mean, about prostitutes using condoms. I've

addressed those issues myself here; what Mgr Loftus makes of them, however, is to to with free speech first of all (9th June column the

The Catholic Times):

'opinions which formerly could only be whispered within what Archbishop Marini recently referred to at the "foetid air of the swamp", can now be spoken openly, as the articulation of the belief of the "Holy People of God", in a fear-free and and fresh-air atmosphere, blown by the Holy Spirit, ...'

And what opinions might those be? Opinions critical of Mgr Basil Loftus, for example? Does that mean that there aren't going to be more underhand attempts to silence his critics? No more shouting down the phone, as

Fr Ray Blake experienced? No more legal bullying, as

Fr Michael Clifton experienced? I've already had a pretty interesting time with letters from the Monsignor. His attitude seems to be: if you've lost the argument, silence your opponent.

So no, I don't think that is what he means. I think he means he can go on using the resources of the Catholic community, such as the newspapers sold in churches, to attack that community's most cherished beliefs, such as the

titles of Our Lady, or the most fundamental principles of the Faith, such as the doctrine of sin. Here is what he says about that:

Inexorably the Church is now going to have to revisit the vexed question of what constitutes sin. In the classical moral theology position sin is committed when the moral law is broken. From that moment, and by that act alone, sin becomes 'ontic'--in other words, it "exists". [It has to exist, of course, to be matter for the Sacrament of Confession: something Loftus seems to have forgotten.]

All that can then be done is to seek some form of mitigation--through imperfect knowledge, lack of full consent to the 'sinful' act, or overall lack of mature judgement in general.

But more and more moral theologians are anxious to establish that sin does not "exist", does not become "ontic", if someone genuinely believes that an act is not sinful, even though it breaks moral law. They are not sinners if they do not believe that, in all the specific concrete circumstances, their act was sinful. The mere breaking of a moral law does not then, in itself alone, and divorced from paticular considerations, necessarily constitute sin. The judgement belongs in no small part to the individual. The sense of personal responsibility for sin in part and parcel of the personal inspiration of the Holy Spirit. Theologians such as Jozef Fuchs [died aged 93 in 2005]

and Sean Fagan [octeganarian Irish theologian condemned by the CDF for advocating women priests: not exactly the rising generation]

have not invented the 'new' approach to sin. They have merely articulated the faith which the Holy Spirit has put into the hearts of the People of God, who cannot err in matters of belief. [The Holy Spirit or the people??]

This personal faith is not in contradiction to the teaching of the magisterium of the Church, but filters and refines its acceptability and interpretation. [??]

The classical Church teaching on sin is reminiscent of St Paul's observation that when he was a child he thought like a child. ...But we are not children. We have grown in the faith. We explore, we take personal responsibility. ...part and parcel of this approach is that as the People of God we will also help to put right the errors of emphasis and interpretation which have grown out of authentic Church teaching.'

This illustrates Mgr Loftus' favourite trick, of leaving it just a little unclear whether he is giving his own views or talking about other people's. But looking at the ideas which he is, let us say, 'exploring', we are faced with an even bigger ambiguity.

On the face of it he could be making a very simple point which can, in fact, be expressed within the 'classical' position: those who genuinely believe they are not sinning are clearly not committing mortal sin, and we can further say that their sin, while 'objective', is not 'subjective'. Subjectively speaking, what they did was not a sin. Of course this raises the question of how far the 'erring conscience' can extend, given that the Natural Law cannot be erased from our hearts. The Nazis who seemed so convinced that killing Jews was morally good won't get off that easily. The corruption of their consciences which led to those beliefs must have been at least partially their responsibility, and the humanity of their victims is not something which they could ever completely forget.

But unless you are determined to force the sense of Loftus' words into the straitjacket of orthodoxy, the tendency of this passage appears to be much more radical. The suggestion seems to be that whatever the 'People of God', or even just 'the individual', decides is the right thing, just is,

ipso facto, the right thing. The contrast between (subjective) sin and the 'moral law' seems to disappear at a certain point, and instead we find him talking about the individual's judgement of the precise circumstances of the case, and a grown up 'taking responsibility'. If you look at the circumstances of the case, and come to a conclusion (killing is usually wrong, but maybe we can make an exception for Jews), then the suggestion seems to be that you are actually infallible, at least if there is a group of you and you can parade yourself as the 'People of God' (or should that be, the Volk?).

I use an extreme example - Nazi anti-semitism - to test the implications of Loftus' ramblings, because it is typical of theological liberals and philosophical subjectivists to focus exclusively, when talking about how people should be allowed to do whatever they like, on a narrow range of examples which they have themselves already decided that people should be allowed to do: say, use contraception, or divorce and remarry. But if contraception is to be allowed for no reason other than that people are tempted to use it, then what of the kinds of wrongdoing that even liberals still reject?

What Loftus is doing here is fundamentally dishonest. First, by refusing to make clear whether he is talking, at different points, about objective or subjective wrongdoing. Second, by refusing to make clear whether he endorses the position he discusses. And third, by presenting in plausible terms a view which is absolutely toxic: that it is 'childish' to take the objective moral law seriously, and that somehow the Holy Spirit guarantees that what people convince themselves is right, is right.

This won't do, Monsignor. It's not big and it's not clever. And it's not new either: not even your antiquated theological exemplars, Fuchs and Brady, thought it up, the precursors of this rubbish belong in the 19th century or even earlier. Loftus' inability to name a theologian under 80 who agrees with him is, perhaps, the ray of hope which shines through the article despite all his best efforts. The Church may be going through a Passion in imitation of her Lord's, but we have the promise of the Resurrection.

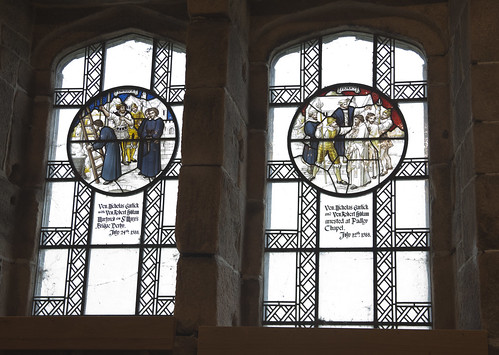

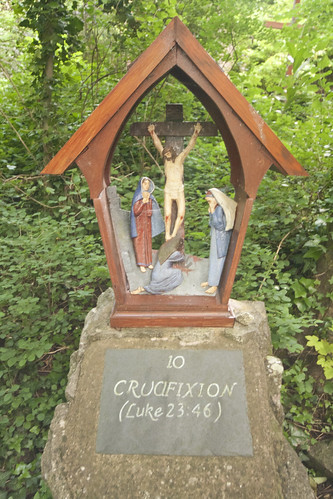

Pictures: Mysteries of the Rosary, from Pantasaph, North Wales,

where we will have our Summer School this year, July 21-28