Pope Francis writes:

Pope Francis writes:A parish must not be 'a self-absorbed cluster made up of a chosen few.' (28)

63: 'We must recognize that if part of our baptized people lack a sense of belonging to the Church, this is also due to certain structures and the occasionally unwelcoming atmosphere of some of our parishes and communities, or to a bureaucratic way of dealing with problems, be they simple or complex, in the lives of our people. In many places an administrative approach prevails over a pastoral approach, as does a concentration on administering the sacraments apart from other forms of evangelization.'

88: 'Many try to escape from others and take refuge in the comfort of their privacy or in a small circle of close friends, renouncing the realism of the social aspect of the Gospel.'

This is a theme he has developed before, and I blogged about it here. I drew attention there to two things: what Pope Benedict said about celebration of Mass versus populum creating a 'closed circle', and what the sociologist Anthony Archer said about the post-Conciliar developments such as prayer-groups, house Masses, and parish committees appealing to cliquey middle-class types and not to the Church's working-class base.

In this and the next post I want to develop a couple of other ideas. The first, for this post, is the question of whether those attached to the Traditional Mass can justly be regarded as a 'closed group'. The other is about closed and open liturgy.

Part of Pope Francis' notion of the closed and self-absorbed is connected with his critique of judgmentalism. Thus (94):

'A supposed soundness of doctrine or discipline leads instead to a narcissistic and authoritarian elitism, whereby instead of evangelizing, one analyzes and classifies others, and instead of opening the door to grace, one exhausts his or her energies in inspecting and verifying.'

The reference to 'soundness of doctrine' suggests he has in mind conservative groups which pride themselves on their orthodoxy, as does the reference to authoritarianism, though of course others can be pretty smug about their doctrinal superiority, and abuse positions of power, as well. It can't apply to trads, of course: we can't be authoritarian, as we are invariably excluded from exercising authority... Neveretheless, in general terms it might appear that the closed community idea is or at least can be linked to a holier-than-thou conservatism. On a conception of the Church in which traditionalists are regarded as extreme conservatives, then trads are in trouble here too.

I have argued already that trads are not best understood as extreme conservatives. But let me put the situation another way. What Pope Francis is wary of here is a self-appointed gang of perfecti - to use the Catharist term - who are more interested in criticising others than in spreading the gospel. I'm sure we've all seen this kind of thing; no group within the Church is immune from this temptation. We all think we are right - by definition, we believe what we believe - and thinking others are wrong can lead to an 'I'm all right Jack' attitude instead of a more positive response, such as dialogue with those with whom one disagrees, or putting one's ideas into some kind of evangelical action.

There are ideas, however, which push those holding them towards the negative, and away from the positive, options here. These are ideas which give us the impression either that others don't need the Gospel, or that they are incapable of receiving it, or both. These ideas are, of course, incompatible with the Christian message, but they are held by those liberals who think that non-Catholics are just as well off lacking the sacraments, and non-Christians lacking the revelation of Jesus Christ. Pope Francis goes to some lengths to oppose these ideas in the Exhortation, as I will show in a later post; they are, of course, directly hostile to the project of evangelisation. Much as I am irritated by the smug superiority of neo-conservative Catholics who think they have all the answers (having just dreamt them up), this is not a problem characteristic of them, or of Traditionalists either. The real danger - whether Pope Francis had this in mind or not - of Catholics getting into little groups to analyse and categorise everyone else, and not bother actually evangelising, is to be found among the liberals.

I am sure many readers of this blog have had the experience I have often had, of a liberal interlocuter giving you a pitying look as someone so backward, unenlightened, and childish, as to take seriously the teachings of the Church, such as Our Lord's physical resurrection from the dead. They are so superior to this way of thinking that they don't even think it necessary, always, to argue about it, any more than they would tell a small child that Father Christmas doesn't exist. From their lofty, indeed Promethian heights, they look down on all the different Faiths as expressing in different terms the pure Truth which they alone have been given to grasp in its fullness. They think the rest of us are incorrigible, but it is they who are incapable of receiving the message of the Gospel: in the famous phrase of the American liberal nuns, they have 'moved beyond Jesus'. They represent the complete closure and indeed death of a Catholic community.

|

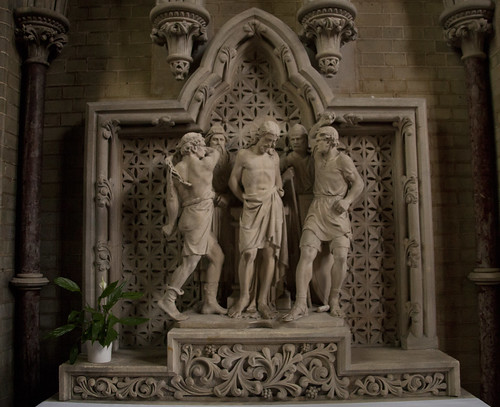

| All these people are looking at Someone else. |

.jpg)