Labels

- Bishops

- Chant

- Children

- Clerical abuse

- Conservative critics of the EF

- Correctio Filialis

- FIUV Position Papers

- Fashion

- Freemasonry

- Historical and Liturgical Issues

- Islam

- Liberal critics of the EF

- Marriage & Divorce

- Masculinity

- New Age

- Patriarchy

- Pilgrimages

- Pope Francis

- Pro-Life

- Reform of the Reform

- Young people

Tuesday, October 02, 2018

The death penalty in the Catholic Herald

Greg Whelan (Letters, 14th Sept) claims to be ‘mystified’ by the widespread concern of Pope Francis’ reversal of the teaching of the Church on the subject of the Death Penalty.

He reminds us that the Church has ‘changed its mind’ about the best punishment for various offences. However this is hardly the matter at issue. The crimes he mentions, such as fornication, are still condemned by the Church as grave sins. What Pope Francis appears to be claiming is the discovery of a new grave sin, that of using the death penalty, even when it might be considered most appropriate.

The penal code found in the Old Testament was in force only for a specific group of people for a specific period of time. Other times and circumstances require other legal solutions. It is preserved for us in Scripture, however, because it teaches us about the seriousness of the crimes it condemns and the importance of the search for justice. Among other things, as St Paul reiterates (Rom13:4), it makes clear that the Death Penalty can rightly be used.

Monday, October 01, 2018

Fr Francis Doyle and St Mary Magdelen

Sir,

I must take issue with Fr Francis Doyle (Questions and Answers, 14th Sept), who dismisses the traditional identification of the 'sinner' who anointed Jesus' feet with nard with Mary of Bethany and with Mary Magdalen, as a mere 'confusion'. No doubt he would be equally dismissive of the further identification of Mary Magdelen with the 'woman taken in adultery'.

The Latin Fathers of the Church held that these people are the same, and this view has become embedded not only in art, but in the liturgy. In the pre-1969 calendar the feast of St Martha (29th July) is the octave of the feast of her sister St Mary Magdalen (22nd), and in the Dies irae, sung at Masses for the dead, the penitent sinner forgiven by our Lord is called 'Mary'.

Should the views of the Fathers and the testimony of the ancient liturgical tradition, be dismissed out of hand? The Second Vatican Council certainly thought not, directing that future translations of the Psalms conform to 'the entire tradition of the Latin Church' (Sacrosanctum Concilium 91). The 2001 Instruction Liturgicam authenticam notes similarly that translations should reflect the 'understanding of biblical passages which has been handed down by liturgical use and by the tradition of the Fathers of the Church .'

Fr Doyle owes this view of St Mary Magdalen a little more respect.

Yours faithfully,

I've written on this specific issue in more detail here.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Tuesday, August 29, 2017

Crying rooms in churches: a terrible idea

|

| Adults and children kneel for the Consecration at the St Catherine's Trust Summer School |

I was inspired to write it by realising that the notion of excluding children from the rest of the congregation, or even from Mass entirely, was an idea with a following among not a few conservative and traditionally-minded Catholics. It is a reaction against the experience of chaotic liturgy where children are allowed to wander around, perhaps even into the sanctuary, which I suppose is more associated with a 'progressive' liturgical attitude. The thought would be: if we want a well-ordered, reverent liturgy, we need to get the small children under control; since we can't rely on parents to do this, we should bundle them into a separate space where they won't spoil things for everyone else.

This is short-sighted, however: as I explain the article, children won't learn to behave if shoved into a room where they can behave as badly as they like, and their parents won't learn to discipline them in that context either. Neither the parents nor the children will experience the atmosphere of the liturgy, and both are left with the impression that they are not truly welcome.

Monday, November 21, 2016

Is Brendan O'Neil a snowflake?

I'm reposting this from Facebook, with a little extra commentary.

I'm reposting this from Facebook, with a little extra commentary.---------------------

Thus far FB. For my temerity in noting these events, I have now been blocked and unfriended by O'Neil.

The alliance between Catholics and libertarians is always strictly tactical, not strategic, as I've pointed out a few times on this blog. What is interesting is that O'Neil has behaved in exactly the way that what he calls the 'snowflakes' of the left have behaved, for which he has been lambasting them for years. They proclaim their openness to ideas, they talk about free speech, but when challended by actual, scholarly, arguments about something they hold dear, they throw their toys out of the pram.

Clearly, the idea that '15th century monks' were evil and oppressive is just too close to his heart for O'Neil to brook dissent. The funniest thing, really, is the idea that 15th century monks, or indeed monks of any century, somehow had a 'dominion over truth'. This is Dan Brown merging into Philip Pullman, on speed. Long before the 15th century there was a brisk non-monastic, commercial book-copying industry in London and the University towns. The monks were important in preserving classical learning in the early Middle Ages, but a funny kind of 'dominion over truth' that was: copying books they didn't agree with being more or less the opposite of Brenden O'Neil's social media policy.

Support the work of the LMS by becoming an 'Anniversary Supporter'.

Sunday, June 05, 2016

Rogue bishops and Traditional Institutes: Letter in The Tablet

It sadly reflects the intellectual and journalistic standards of The Tablet the Lamb goes on to try to make this a stick to beat the Traditional Institutes and orders, and uses the Franciscan Friars of the Immaculate to do so.

This ruling is clearly targeted at the large number of traditionalist religious orders that have sprouted up in recent years, many of them exclusively celebrating the sacraments in the pre-Vatican II Old Rite. Many of them do good work but there are suspicions about others.

Saturday, June 04, 2016

Esperanto vs. Latin

|

| Last year's Summer School - a bit of Latin is included, naturally. Details for this year are here. |

Saturday, February 06, 2016

Prayer or bedlam before and after Mass? Which would God prefer?

|

| Cardinal Burke leads the Prayers After Low Mass following his Prelatial Low Mass in SS Gregory & Augustine's, Oxford. |

SIR – Chris Whitehouse (Letter, January 29) makes the same mistake as many others who, like him, seek to justify the bedlam in many Catholic churches immediately prior to and after Mass on the grounds that “God doesn’t mind”. Fortunately we do not have to rely on such intuitions about what would please God in his house, as God’s express position is an unequivocal: “My house is to be called a house of prayer.”

Monday, January 25, 2016

Promoting the Traditional Mass, then and now: Letter in the Catholic Herald

|

| St Mary's, Warrington: stuffed with regular parishioners experiencing the EF for the first time, thanks to the arrival of the Fraternity of St Peter. |

You report Mgr Charles Pope as warning that the popularity of the Traditional Mass may have 'reached its peak' (The best of the blogosphere, 15th Jan 2016).

Mgr Pope observes that in the early 1980s, Traditional Masses were often packed to the doors, but that things are different now. This is perfectly true, and is not due only to the fact that fewer Masses were on offer back then. In 1980, under the brief editorship of Christopher Monckton, the Universe conducted a survey of Catholics which showed that half would attend the Traditional Mass, were it available. Today, only a small minority would know what you were talking about.

Friday, November 04, 2011

Cups and Chalices, again

Note the glorious fantasy of the Aramaic Gospels. This version only exists today in the fevered imaginations of biblical critics, and probably never existed anywhere else. What weight does an imaginary text have in this debate? Does the Church teach that imaginary documents are inspired by the Holy Spirit?

So her objection, to repeat, is not to the translation, but to the Latin original. She, like many of your correspondants, is rejecting the theological aptness of the 1969 Mass, and of the entire Western liturgical tradition which lies behind it, in relation to this exact phrase.

However, I fancy her objections are based on a misunderstanding. While the chalice may, or may not, have been precious in terms of human craftsmanship, it was certainly precious in terms of its contents. And as the Church accepts Tradition as a source of dogma alongside Scripture, the Roman Canon has its own theological authority.

Thursday, November 03, 2011

Mass of Ages relaunched!

The first edition of the new-look Mass of Ages, produced by our new editor Gregory Murphy, is now available. It is on its way to LMS members, and can be purchased from a number of Catholic bookshops, as well as directly from us on-line.

The first edition of the new-look Mass of Ages, produced by our new editor Gregory Murphy, is now available. It is on its way to LMS members, and can be purchased from a number of Catholic bookshops, as well as directly from us on-line.Friday, October 07, 2011

Is the Roman Canon vulgar?

This is a question posed, by implication, by Dom Sebastian Moore OSB, in a letter published in The Tablet last weekend (1st October).

This is a question posed, by implication, by Dom Sebastian Moore OSB, in a letter published in The Tablet last weekend (1st October).The substitution of the word “chalice” for “cup” in the Eucharistic Prayer has already been noted. The unconscious vulgarity of this change, at the most dramatic moment in the whole liturgy, is horrifying, as though the dignity of the word “cup” were not upheld by the hands that held it and passed it round, and to “improve” on this is to make of another good word a genteelism which betrays the mentality of the translator – and three times! It confirms all that we now know, thanks to The Tablet’s preparatory articles, about the process whereby this translation was arrived at.

(Dom) Sebastian Moore OSB

Downside Abbey, Somerset

(That's his photo, from his blog.) They have published my reply:

Dom Sebastian Moore repeats yet again in your letters pages (1st October) the suggestion that the use of the word 'chalice' in the new translation of the Missal is wrong. It would be astonishing if he or anyone could seriously claim that 'he took the cup' is an accurate translation of 'accipens et hunc praeclarum calicem in sanctas ac venerabiles manus suas'. If the authors of the Roman Canon had wished to avoid what Fr Moore regards as 'vulgar' they would certainly not have used such flowery language, and substituted a more prosaic word like 'poculum' ('cup') for 'calix'.

It is clear that Fr Moore and your other correspondents are not objecting to the new translation at all, but to the Latin original. This has been used continuously by the Roman church since the time of Pope St Gelasius I, who died in the year 496. Alas, I think the consultation period may have closed.

Yours faithfully,

Joseph Shaw

Chairman, The Latin Mass Society

It makes no sense to suggest that the elevated language of the new missal translation is wrong but the even more elevated language of the original Latin is ok. As well as its frequent doubled adjectives ('holy and venerable') and other poetic tricks the Latin makes free use, for example, of archaism, which has not been allowed in the translation, exotic foreign words, and words only ever used in the context of Christian Latin. If the new translation is vulgar, the Roman canon must be utterly bourgeois.

The idea that only 'nobly simple' things avoid vulgarity, which rejects with disgust not only the Roccoco but the Gothic, which prefers the monotone to the melisma, is thankfully a fad passing away with Fr Moore's generation. It is small minded, petty, and parochial. What person of taste can tolerate only one style, and one, indeed, of only a handful of artists working in only a few decades corresponding to the formative period of their own lives?

Fr Moore's generation had their fun razing irreplaceable altars and dynamiting exquisite churches which they were incapable of understanding. He should allow the painful work of restoration go on without further interference.

Sunday, October 02, 2011

Letter of the week, from the Catholic Herald

Sir,

I write as a "tortured liberal" Catholic ("progressive" on most of the predictable issues). Yet I recently found myself joining both the Latin Mass Society (LMS) and the Association for Latin Liturgy (ALL), in exasperation at our bishops' response earlier this year to Universae Ecclesiae, following that made to Summorum Pontificum in 2007.

Apparently, current provision of the Extraordinary Form (EF) needs no expansion and curriculum pressure in seminaries precludes accommodating the requested formation in Latin and the EF. Is this really the "generous" welcome these documents ask of our hierarchy?

I have concluded that it is only by supporting organisations such as the LMS and the ALL that the Holy Father's explicit wish to restore and extend the use of Latin in the liturgy has any hope of making progress. These bodies' EF and Ordinary Form Masses, other services, with the courses in chant, formation for priests, servers and faithful in the Mass and the Latin language, all seem to chime with the current liturgical renewal and reinforcement of Catholic identity agenda. Indeed, one might expect our dioceses to be undertaking such initiatives.

I recently attended two EF Masses at St James's, Spanish Place, after an absence of nine or 10 months. I estimate that the congregation had doubled in that time, comprising a wide range of age, class and ethnicity: someone is clearly doing something right here.

The Tablet's coverage of World Youth Day in Madrid noted that the Pope celebrated most or all of his Masses in Latin, but that his youthful congregations were largely unable to deliver their responses. His Holiness seems to expect young Catholics to cope with the liturgy in Latin, so I wonder what strategies the Hierarchy has in mind to enable them to do so.

At the time of Summorum Pontificum Pope Benedict expressed the hope that the two forms of the Roman Rite would come to "learn from each other". I would like to know how it is planned to take this cross-fertilisation process forward in England and Wales.

The English and Welsh bishops have a stated view (from 1966) on the position of Latin in the post-conciliar Church: "Every encouragement should be given to reciting or saying the Ordinary of the Mass in Latin ... definite steps must be taken to see that knowledge of the Latin Mass is not lost... The use of Latin will be encouraged in the new Mass as it has been in the old; Latin expresses the nature of the Church as international and timeless."

How do our current bishops prosecute this agenda?

Peter Mahoney

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

Where is the barrier, Mr Mickens?

I quote this spiteful description because of the identifiable falsehood: as we've all seen from the photos, there was no barrier. Either Mickens was making it up, or (more likely) he was relying on a garbled second hand version. What is clear, however, is that he didn't bother talking to any of the 'kids' involved or looking at the pictures on the Internet, which went up within hours of the events they captured.

Where is the barrier, Mr Mickens?

Where is the barrier, Mr Mickens?

What a terrible thing photography and the Internet are for liberal fantasists like Robert Mickens. We don't have to take their word for anything any more.

There should be a short article on this confrontation in the next Mass of Ages giving the story from the horses' mouth - from the young chap in the middle of the photo.

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Liturgical conflict in Bristol

There is an interesting letter in the Catholic Herald this week (12th August), by a certain Brendan McBride, rejoicing in the loss of the Church's liturgical traditions.

There is an interesting letter in the Catholic Herald this week (12th August), by a certain Brendan McBride, rejoicing in the loss of the Church's liturgical traditions.

'I was born and brought up when the priest said Mass with his back to me in a language I did not understand. Women covered their heads in church and no girl altar servers were allowed. To receive Communion I had to kneel at a barrier between me and the sanctuary and stick out my tongue. In those days the priest and the people inhabited different sacramental worlds; thank God such days have gone.'

He goes on to describe the Mass he attends in Bristol (ie presumably Clifton) Cathedral. Of the celebrant:

'We see his smile when calling us to prayer, and he sees ours when we respond. The altar is wide open and at Gospel time the younger children scamper up the steps to sit beside him--he is wonderful with children--while he tells them Bible stories...'

There are altar girls and Extraordinary Ministers of Holy Communion. The writer practices intinction: 'I take the Host in my hand and dip it in the chalice wine.'

It's all down to Vatican II, which 'recovered for us all the simplicity of the communial meal that He institured, one in which He gathers His friends to Himself as He did the night before He died. Communion with Him is not an occasion of adoration, nor one calling for "an atmosphere of focus, solemnity and mystery", but for intimacy and the happiness it brings.' He is very grateful to Bl Pope John XXIII, surprisingly, since the poor man would have been even more horrified than most of the Council Fathers at the liturgy Mr McBride descibes.

Not everyone in Bristol is taking the love-feast so well. This week's Universe (14th August) carries a letter given the title ' 'Unpleasantries' of the Sign of Peace', from A.W. Whaits, Bristol.

Whoever dreamt up the sugary sign of peace seems to have been naively oblivious to some unpleasant practicalities.

In my church, one elderly widower tours the pews 'making a meal'; of his license to to make contact with female bodies. ...

When the 'feel good' moment arrives, they approach me expectactly, but I ignore such cheap, shallow, bonhomie. I have often felt like adding 'a little peace before Mass would not have gone amiss.'

One man's 'intimacy, and the happiness it brings' is another man's invasion of personal space. I wonder if these two individuals have ever sat beside each other in the pew, and what happened at the kiss of peace.

Leaving aside the question of liturgical law, the real problem with Mr McBride's liturgy is that it depends, for its success, on a number of things which are not widely available.

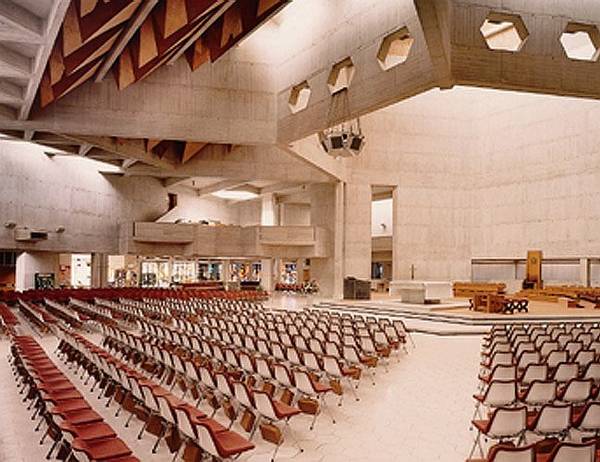

First, architecture. Clifton Cathedral is famous for its modernist architecture; it was built for the liturgy McBride describes, but very, very few Catholic churches were. So while Clifton Cathedral is not to everyone's taste it has a coherence and integrity which few Catholic places of worship have, once they have been smashed up and rearranged in an attempt to create an atmosphere for which they are utterly unsuited.

Second, clergy. The Dean of Clifton Cathedral is 'wonderful with children'. That is very nice to hear. 'Wonderful' implies 'far above average'. Half our Catholic clergy are, by definition, below average in their ability to deal with children. (Only children themselves have the privilege of being 100% above average.) So what are they supposed to do? The liturgy described by McBride clearly depends on the Dean's remarkable personal qualities. Without them, it would fall flat.

Third, the faithful. Bristol is a populous city and the Cathdral's distinctive liturgy no doubt draws a good congregation from accross the city. People who like it must seek it out. I am happy for them. But what about priests who have to serve all the Catholics in their parishes? Not just the smiley ones who love touchy-feely services, but the curmugeons like A.W. Whaits. Even Clifton Cathedral's Dean might find his talents stretched to inject enthusiasm into a congregation made up, like the general Catholic population, 50% people coming out of habit, with little clue about what is going on, 30% curmudgeons going with gritted teath, and 20% liberal enthusiasts. We've all seen priests try to deal with this kind of congregation, and it can be a painful experience for all concerned.

The hyper-liberal liturgical experiment is something which by the very nature of things can work (at least superficially) very well in certain settings, but simply cannot be replicated across the country. The attempt by bishops and individual priests to impose it in the wrong conditions has had disasterous consequences. But in the liturgical orthodoxy of the last generation, they had nothing else to try.

But now things are changing.

First Mass of Fr Matthew McCarthy FSSP in the chapel of the Carmelite Convent of Jesus Mary & Joseph at Valpariso, Nebraska. More photos. The Chapel and convent are new; the priest is newly ordained, the chapel is full of families with young children, the convent is full of young nuns, all committed to the Traditional Mass.

Just for fun, here's a taste of the kind of liturgy Pope John XXIII used to preside over.

Friday, August 12, 2011

The Reform of the Reform, and a more peaceful alternative

I'm in favour of these things because they are good in themselves, and because making people aware of these things ipso facto undermines objections to the Church's liturgical traditions. People say: surely it is bad to emphasise the difference between priest and people? Surely it is unnecessary to grovel before the Blessed Sacrament? Surely the most important thing with a liturgical text is that it is instantly understood by an uncatechised 5 yr-old? It is the 'surely' which is the most irritating part, since the claims run counter to the whole tenor of the Church's liturgy, and the Temple liturgy before that, since at least the time of Moses. We need to expose Catholics to a liturgy in which makes these platitudes seem less obvious: to introduce them to the idea that what we are engaged in is worship, in which sacred gestures, clothes, postures and languages are actually appropriate.

So Reform of the Reform gets the thumbs up from me. The practical question is whether a priest is better off making incremental changes to his existing parish Masses in the direction of resacralisation, or introducing the Extraordinary Form. And although these are not mutually exclusive, the debate gets interesting here.

For this is where the argument I noted in my last post come in. To repeat it, I have heard it said:

1. People will hardly notice the difference between Latin OF and the EF.

2. People who will happily accept the Latin OF will be very upset about having the EF imposed on them.

3. The differences between OF and EF are of no real importance (conclusion from 1).

4. It is not worth causing a row in the parish by using the EF when you can bring in the Latin OF instead (conclusion from 2 and 3).

Now what looks thoroughly silly when set out on the screen can actually dominate one's thinking if one isn't careful, and this seems to be happening with some proponents of RotR. The EF - they say - is a bridge too far, we'll never get people to accept it - or, at least, not soon. But we can do something: we can improve the Novus Ordo right away, and keep on doing this till it's practically indistinguishable from the Traditional Mass. Er, right.

The problem is that the objections which people have to the EF are exactly the same as the objections they have to the 'practically indistinguishable' OF. And they will raise those objections at every step of the journey from the familiar OF to the Reform of the Reform OF. So the first question comes down to this: is it better to have a decade of trench warefare over 100 incremental changes, or a month of high-intensity conflict when you've introduced all the changes at once? The World War I Western Front, or 'shock and awe'? Whether the end result of the changes is a Latin Novus Ordo with all the bells and whistles, or the TLM, is less important - and if you really think they are indistinguishable, then it's not important at all.

It is far from obvious that the trench warfare option is always preferable. I suppose the answer will depend on local conditions, including the character of the priest. But actually it is the wrong question. Because you almost never have only one Mass in a parish to consider.

John Hunwicke, writing in the current Mass of Ages (the magazine of the Latin Mass Society), gives the example of Anglo-Catholics in the 1930s who imposed the Roman Rite on unsuspecting parishoners in place of the Book of Common Prayer, and faced an unsurprisingly strong reaction. (One parishoner placed a dead donkey on a vicar's doorstep.) Isn't it better, he asks, to move gradually? Not necessarily, as I've just explained, but the real point is that Catholic parish priests are in a completely different situation. In a 1930s Anglican parish you'd only have one Communion service (if that) on a Sunday, with Matins before it and Evensong in the evening. The Anglo-Catholic vicar's obvious move was to change from the Prayer Book to the Roman Rite for this one service. But in a modern Catholic parish you will have two or three Masses on a Sunday, and many have more. No Catholic priest today, wanting to increase the sacrality of his services, is going to change all of them to the TLM overnight. He will either change one of them, or, more likely (if the time in the parish timetable exists, and if he has the energy), create a new Mass slot and put the EF in that.

So a new priest arrives in a parish with, say, two or three Sunday Masses, which each seem to him seriously deficient from the point of view of sacrality. There are entrenched groups of liturgical planners, people composing bidding prayers, folk musicians, Extraorinary Ministers of Holy Commuion, lay readers, altar girls, and leaders of children's liturgies, in each of these Masses, and they all know the Bishop's postal address, and probably his phone number too. So what does he do? The RotR crowd would suggest: introduce a bit of Latin, a bit of chant, use the Roman Canon, encourage communion on the tongue, get rid of the guitars, cut down and then eliminate the EMHCs, and then more, and more, and more, along the same lines.

Following this advice with vigour will lead to one or both of two things for the priest: a nervous breakdown or a transferral to Outer Mongolia by the bishop. Following this advice with sensitivity and astuteness, low cunning and the weapons of spiritual warfare, will perhaps lead to the priest making gradual progress and suffering a bloodless martyrdom in the process. But there is an alternative: introduce the Traditional Mass into a currently vacant spot.

Suddenly, you are building on a greenfield site. There are no entrenched special interests. If anyone asks why you are using Latin or Chant or the Roman Canon or only male servers you say 'I'm afraid I have to - it is part of this Form of the Mass.' People who don't like it won't go. But as time goes on it will gather a congregation and gradually the priest has allies in the parish, people who will do things for him and defend him from attack. And they, and the Traditional Mass itself, will have a gradually transformative effect on the whole parish.

People will still complain, because some people just hate the Traditional Mass. But to complain to the bishop 'Fr X has introduced an EF Mass to which I never go' is so obviously absurd, and what the priest has done is in such obvious accordance with Summorum Pontificum, that the priest is in a vastly stronger position than in the RotR scenario.

Of course there are complications. In some parishes it is impossible to introduce an entirely new Mass, though the general principle remains: by leaving most of the Masses more or less intact, having one EF Mass will attract less, and less reasonable, criticism. Again, there may be things happening in those OF Masses which simply must be stopped without delay: serious liturgical abuses. But in dealing with these the priest is in a much stronger position than when trying to get the folk group to learn Gregorian Chant. After all, whether we like it or not, Chant is not obligatory in the Ordinary Form.

The point here is not that this strategy creates a perfect situation overnight. But given that we all understand that it will take a lot of time to get the liturgy in the parish where we want it to be, what kind of policy will work best? To make a frontal attack on the vested interests in their entrenched positions, or to outflank them: doing something it is harder for them to oppose, but will have just as much, and probably far more, effect on the overall liturgical atmosphere of the parish as time goes on.

The general point is this: jumping straight into the Traditional Mass is actually a way to resacrilise the liturgy in a parish in a more serene manner than attempting to steer existing OF Masses in the Reform of the Reform direction. You are less likely to have people complaining to the bishop. You are less likely to have people lapsing or going to other parishes. It is not a choice between 'shock and awe' and the Western Front: there is an alternative, and unsurprisingly the priests saying the EF in England and Wales today have all done exactly what I have described.

It remains to those many priests, not yet committed to the Extraordinary Form, who are concerned about sacrality, to realise that the best way to address the problem is not by arguing with the liturgy committee, the folk group, and Uncle Tom Cobley about having the Sanctus in Latin this week, but by learning the Traditional Mass, and introducing it into parish life as something in addition to, not instead of, the Ordinary Form. This won't solve all your problems overnight, but it will set things moving in a positive direction.

Photos (apart from the military ones!): Low Mass on a Sunday evening in St George's Warminster, said by Fr Bede Rowe, the LMS Regional Chaplain for the Southwest. Fr Rowe introduced this Mass in addition to his other masses soon after arriving in the parish. See my post here.

Thursday, August 11, 2011

Latin Novus Ordo and the TLM: can you tell the difference?

Asperges: not something you'd fail to notice.

I have just read somewhere someone being quoted as saying that if unless you are liturgical expert you'd hardly be able to tell the difference between the OF in Latin - the 1970 Missal - and the EF - the 1962 Missal. It doesn't matter where I read it or who was being quoted, because I've heard this dozens of times. And it doesn't make any more sense on the umpteenth repetition.

The Gospel: proclaimed from the North side of the Sancturary in a Solemn Mass, here, or from the North end of the Altar, at a Missa Cantata, not from a lectern or ambo.

So you go to your local parish where they always do Mass in Latin in the OF (I know, these are in single figures in the UK but bear with me) and, when the priest comes in, instead of going round the altar and saying the Introductory Antiphon (probably after waiting for a vernacular hymn to finish) he starts a chant you've never heard before and sprinkles the people with holy water. Oh and he's wearing a completely different vestment, which he then very publicly takes off in order to put his usual one on, but you still don't get the Introductory Antiphon; instead he starts a long dialogue with the servers, and when that's over he doesn't go round the altar at all, but stays on your side of it. You then notice that the altar is set up differently, with candles and crucifix at the back, and that there are no altar girls. And the music has been completely different, with the choir singing the Introit and the Kyrie without a break.

Communion distributed to the faithful kneeling and on the tongue. And spot the mantilla!

But hey, you don't notice any of this because you're not a liturgical expert. But perhaps you'd notice that the Gospel is sung in Latin - yes I know you can do that, and some of the other things I've mentioned, in the OF, but it is about as common as having the sermon in Latin, and if we are talking about what people notice we should stay with what actually happens, and not what is theoretically possible. As well as having the readings chanted in Latin, the lectern is not used. If you've still not noticed that things are different today, the canon of the Mass is said silently. Oh come off it, if you don't notice that then you're either deaf or asleep. Maybe you'll wake up in time for the Last Gospel.

I've just used the example of Sung Mass on a Sunday. It is commonly said that the EF-OF contrast is less striking with Sung Mass and this is true, mainly because of the way the congregation can join in with some of the responses, probably using the same tones. On occasions where there are more clergy present, the difference between a Solemn Mass, with deacon and subdeacon, on the one hand, and a group of priests concelebrating, on the other, is so manifest that it is hardly necessary for me to spell it out.

The consecration at a Solemn Mass.

If I were to compare Traditional Low Mass with an OF Latin Mass without music the differences would be even more evident. The Prayers at the Foot of the Altar dominate the opening sequence of events and the responses being made by the server alone give the Mass a very different feel, as does the priest celebrating ad orientem. And yes I know that in a few places the OF is celebrated ad orientem but that is neither typical nor what is recommended by 'the rules', the current edition of the General Instruction of the Roman Missal. If we are talking about a priest following 'the rules' then we must be consistent. (For a side-by-side comparison of the texts, see here.)

A random photo of a concelebrated Mass. Not something easily confused with a 1962 Missa Solemnis.

When I see a really silly claim like this, repeated by apparently sane people a great many times, I want to know what the motivation is. Why do so many people want to minimise the difference between the different forms of the Roman Rite? It may be that they think this is necessary to underpin the claim that both are valid (in all senses of the word) celebrations of the Sacrament of the Holy Eucharist, but I don't hear them claiming that only an expert would notice that he'd wandered into a Byzantine Rite church on a Sunday morning.

Then again, it may be that the argument goes like this: there are surface differences and there are deep differences. The non-expert won't notice the deep ones, and the surface ones are only surface, so they don't matter. This may indeed be at the back of the minds of the people saying the differences are hardly noticeable, especially if they have dismissed in advanced the Asperges and the Prayers at the Foot of the Altar as non-essential, not really part of the Mass. Well maybe, but that's not the same as saying that people won't notice them. Anyway, this argument fails, and for an important reason.

There are indeed many differences between the '62 and '70 Missals which are significant, but wouldn't be noticed, or not understood in full, by a non-expert, most obviously changes to the proper prayers. Going back to the unexpected TLM I was describing, the chap in the pews, if armed with a translation, might be taken aback to hear, for example, the collect of the 4th Sunday of Lent:

'Grant, we beseech Thee, O Almighty God, that we, who are justly afflicted according to our demerits, may be relieved by Thy comforting grace.'

What he won't know, unless he's read up on the issue, is that to create the 1970 Missal hundreds of collects were edited or rewritten to remove references to sin, punishment, merit, grace, and the intercession of the saints. What the newcomer to the TLM will notice, however, is other differences with a similar explanation, such as, in the EF, the use of black for Requiems, and the priest's Confiteor before the server's.

Again, someone following a translation to the EF may be slightly surprised by the reference to 'oblation' at the Offertory, and reflect that he doesn't read that word much in the translation of the Latin OF. What he won't know about, unless he's read up on it, is the consistent effort by the reformers of the liturgy to remove elements which create an ecumenical barrier, of which the notion of oblation is a prime example. What he will, nevertheless, notice, is other things which serve to emphasis distinctive Catholic doctrines, such as the Real Presence, including the priest's genuflection before picking up the Sacred Species, and communion kneeling and on the tongue.

In short, because the reform followed a consistent policy, surface differences are not a bad guide to deep differences. The things people pick up on (and sometimes complain about) when they are used to the Mass in one form and are then exposed to the other form, may not be of huge importance in themselves, but they are frequently illustrative of deep differences of real theological importance.

The biggest paradox of all with the claim that non-experts won't notice the difference is that it tends to be used by people who are actually quite sensitive to what the faithful notice when the liturgy is changed, and are concerned about it. For with the next breath the claim is often made: in order to minimise upset and complaints, if we want to improve the liturgy we should introduce the Latin Novus Ordo into our parishes, and not make the great leap to the Traditional Latin Mass.

So the argument goes like this:

1. People will hardly notice the difference between Latin OF and the EF.

2. People who will happily accept the Latin OF will be very upset about having the EF imposed on them.

3. The differences between OF and EF are of no real importance (conclusion from 1).

4. It is not worth causing a row in the parish by using the EF when you can bring in the Latin OF instead (conclusion from 2 and 3).

The trouble is, claims 1 and 2 are mutually contradictory. (3 doesn't follow from 1 either.)

So this confusion is really about the 'Reform of the Reform' debate, and the best way in practice to improve parish liturgy: something I will post about tomorrow.

Photos, apart from the concelebration, are from Solemn Mass celebrated in St William of York, Reading, by Fr Marek Grabowski FSSP. You can see more about that Mass here.

Monday, July 25, 2011

Smashing the TV

Tim Stanley, an English academic specialising in American history, is actually in Hollywood to research a book about the film industry. He has a fascinating post about the culture of the place, which, he thinks, explains the liberal tenor of its output better than any conspiracy. He writes:

No, the problem that the conservative faces isn’t intellectual, it’s social. Conservatism tends to be raw and unfiltered. In conversation, it punctures the Zen equilibrium that sustains everyone in Los Angeles. The industry works by networks and anyone who can’t sustain a long conversation about the importance of raw carrots and natural fibers to the functioning of Yin and the flowing of Yang won’t fit in. One Right-wing writer told me that following 9/11, he found work dried up. There was plenty of interest in his output (he’s deservedly famous) but when it came to small talk before pitches, or the gossip at the writers’ in LA Farm, he was immediately frozen out. “Peopl e would open with, ‘Isn’t George Bush a moron?’ And I would say, ‘No, I voted for him.’ And I could feel I was losing their respect.”

e would open with, ‘Isn’t George Bush a moron?’ And I would say, ‘No, I voted for him.’ And I could feel I was losing their respect.”

True, this suggests that Hollywood has a leftward prejudice. But the real problem with what the writer said wasn’t the content but the act of disagreement itself. Hollywood conversations deal in hyperbolic affirmations covering for lies: “You’re amazing. That pitch was the best ever. You’re the most beautiful woman I’ve ever met. Adam Sandler is the funniest man alive!” Disagreement and contradiction are acts of verbal rape.

I find this all too credible. It explains how typical Hollywood output is not just liberal, but self-affirming pap. Something pretty similar, I would wager, is going on at the BBC.The seriousness of the problem should not be underestimated. The characterisation and plots of TV shows and films can consistently affirm liberal attitudes without the view

er even noticing. This is discussed in the other article which has come up recently, via CFNews, a book review in The Washington Times (see it here). The book is 'Prime Time Propaganda: The True Hollywood Story of How the Left Took Over Your TV' by Ben Shapiro; it is reviewed by Jeffrey Kuhner. Kuhner writes, of this historical development of the problem:

er even noticing. This is discussed in the other article which has come up recently, via CFNews, a book review in The Washington Times (see it here). The book is 'Prime Time Propaganda: The True Hollywood Story of How the Left Took Over Your TV' by Ben Shapiro; it is reviewed by Jeffrey Kuhner. Kuhner writes, of this historical development of the problem:One of the watershed programmes was All in the Family. The character of Archie Bunker symbolised the progressive caricature of Conservatives -- ignorant, racist and xenophobic. The show frequently denounced the Vietnam War and even celebrated draft dodgers as heroes. It also broke new ground in portraying the father figure, Archie, as a working-class bigot who was less enlightened than his anti-war, socially permissive son-in-law, Meathead (played by the odious leftist Rob Reiner).

'All in the Family' was first broadcast in 1971, and set the tone for the decades which followed. How often have you seen socially conservative or religious characters portrayed in a favourable light? Let me rephrase that: have you EVER seen such a character portrayed in a favourable light in a mainstream film or series? How often have you seen such characters ridiculed and outwitted? How often have such characters turned out to be hypocrites? If there is anything attractive about them, or a streak of honesty, how often have they been converted to a more relaxed, progressive, liberal approach to life? (Has the opposite ever happened?)

This is insidious a

nd poisonous. There are intrinsic problems with TV as entertainment: the tendency of people simply to switch it on and watch whatever pops up, even if rather bored by it, for hours on end. What Shapiro is talking about, however, is a problem not intrinsic to the medium, but accidental: the fact that the people making so much of the programming are peddling a relentless liberal agenda. It makes it even more boring than it would be otherwise.

nd poisonous. There are intrinsic problems with TV as entertainment: the tendency of people simply to switch it on and watch whatever pops up, even if rather bored by it, for hours on end. What Shapiro is talking about, however, is a problem not intrinsic to the medium, but accidental: the fact that the people making so much of the programming are peddling a relentless liberal agenda. It makes it even more boring than it would be otherwise.There are lots of good films, and from time to time there are good serie

s on TV. All of them can be seen on DVD, for hire or for sale. Vast quantities of stuff is becoming available on YouTube and Gloria TV. It is becoming possible to access films and programmes by downloading them (legally, and temporarily) from the internet for a small fee. All in all, the telly is losing its indispensibility as a window onto popular culture. Popular culture is itself increasingly fragmented: it is no longer the case that 'everyone' is watching anything in particular as it is broadcast.

s on TV. All of them can be seen on DVD, for hire or for sale. Vast quantities of stuff is becoming available on YouTube and Gloria TV. It is becoming possible to access films and programmes by downloading them (legally, and temporarily) from the internet for a small fee. All in all, the telly is losing its indispensibility as a window onto popular culture. Popular culture is itself increasingly fragmented: it is no longer the case that 'everyone' is watching anything in particular as it is broadcast.All of this opens up the possibility that instead of making provision for the entire sewer to be delivered to your sitting room every day, you can be selective and choose some decent things to watch from time to time, and stop paying the TV License at the same time. Kuhner concludes his review:

Conservatives have one powerful weapon: They can flip their TV sets off. I have not watched television in years, sparing my senses - and soul - from the ubiquitous onslaught. Hollywood has declared war on Middle America. It's time we declared war on it.

So go on: Catholics: Unplug Your Televisions!

See the CUT website here.

Wednesday, July 20, 2011

Fame at last: LIFE and non-directive counselling

Hanging a story on someone without even asking them for a quote looks like shoddy journalism, but there you are. However I've never been described as a 'leading Catholic figure' before so I can't complain.

In my post (on my deeply obscure 'Casuistry Central' philosophy blog) I summarise objections to non-directive counselling under four headings. I don't say that their policy is wrong; I just seek to identify what the fuss is about. I end the post by saying that LIFE needs to address the arguments, particularly the last, key argument about cooperation with evil, and I explain what form the justification of such cooperation with evil can take, in Catholic ethics.

So do they provide such an argument? Or any argument? No.

Instead we get a quotation from Dr David Albert Jones, the Director of the Anscombe Centre (of which I am a Governor). He chooses his words carefully, and I wouldn't disagree with any of them. Indeed, they are little more than a paraphrase of what I wrote to qualify the 'moral' argument at the end of my original post. This is not as surprising as it looks, since Dr Jones was not responding to my views when he wrote these words: when asked by the Catholic Herald for a quote, he just sent them something he'd written earlier on the general topic.

“There is a certainly a role for directive parents, teachers, preachers, and judges. Nevertheless, from a Catholic perspective, there could also be a role for a non-directive counsellor, if this means someone who aims to help people to come to see these things for themselves. Catholic counselling should always be value-driven but may express these values also by giving someone space to reflect on what their heart tells them.”

Yes, there is nothing intrinsically wrong with not jumping down a client's throat to say things which will make the client more inclined to have an abortion. There is a time to speak and a time to remain silent (Eccl 3.7). The question, which Dr Jones does not address here, is whether faithful obedience of the rules of NDC would prevent a counsellor from avoiding an illicit cooperation with evil under certain concrete circumstances.

Remember, NDC requires counsellors to be non-directive not only when that would aid a pro-life outcome, but also when it would aid an anti-life outcome. It is neutral between outcomes: that's the whole idea.

Here are a couple of examples.

1. If the counsellor knew that information about the nature of abortion, the developmental stage of the baby, or the consequences of abortion for the mother, would influence the client in a positive way, would the counsellor be able to offer this information without being asked?

2. If the client asked the counsellor whether she, the counsellor, thought that abortion was morally licit, and the counsellor knew (having established a rapport with the client) that an tactful but honest answer would influence the client in a positive way, would the counsellor be able to answer?

Neither I nor Dr Jones knows the answers to these questions. They depend on the detailed nature of the NDC guidelines which LIFE uses. What I suspect, however, is that whatever the real answer is, LIFE would prefer its government partners to think that the answer to each question is 'no', and would simultaneously prefer its Catholic supporters to think that the answer to each question is 'yes'.

Tuesday, July 19, 2011

The hermeneutic of rupture

I blogged recently about finding Medieval wall paintings in an Anglican church. What can they think, I said? I managed to offend some-one leaving a comment, though he or she didn't pause long enough to explain how it is supposed to work. Anglicans are proud of these medieval vestiges (after a few centuries of trying to expunge them); these churches often play down the Reformation, saying things like 'we have worshiped here for 900 years' or whatever. And yet they can't claim that the theology and spirituality of a Medieval Doom painting is in continuity with modern Anglicanism (the calvary to the right was near the Doom; it formed the reredos to a nave altar). Ironically, it would be more in continuity with the theology of the people who first white-washed it over in the 16th Century, but that's another story.

I blogged recently about finding Medieval wall paintings in an Anglican church. What can they think, I said? I managed to offend some-one leaving a comment, though he or she didn't pause long enough to explain how it is supposed to work. Anglicans are proud of these medieval vestiges (after a few centuries of trying to expunge them); these churches often play down the Reformation, saying things like 'we have worshiped here for 900 years' or whatever. And yet they can't claim that the theology and spirituality of a Medieval Doom painting is in continuity with modern Anglicanism (the calvary to the right was near the Doom; it formed the reredos to a nave altar). Ironically, it would be more in continuity with the theology of the people who first white-washed it over in the 16th Century, but that's another story.But some people in the Catholic Church have a similar problem. Catholics who openly reject the first 19 Centuries of Catholic practice, spirituality and theology exist, but they are no more common than the fire-eating Protestant Anglicans who would still prefer to erase the Medieval paintings in the parish church. A much larger number of Catholics talk confidently about the Church's great history, and even point proudly at our artistic heritage, while wanting to hear as little as possible about the praxis, theology and spirituality which went with it. Indeed, when talking about the past, they would like to pretend that certain awkward facts did not obtain. Those facts are embarassing.

This is part of what the Holy Father condemns as the 'hermaneutic of rupture'. For a nice example, see this illustration from the Catholic Truth Society's children's book, 'Saint John Mary Vianney, the Cure D'Ars.' Don't get me wrong, I like these books; I own the full set and have read each of them many times to my children. And then again I am very aware that they are translations from the Italian - presumably the illustrations were not commissioned by the CTS, but come from Italy too. (The illustrator is a certain Giusy Capizzi.) However, it illustrates the point all too well.

Looking in the St Paul's Bookshop in Westminster the other day, I saw a very similar illustration in the children's Life of St John Vianney published by St Pauls. Is it too embarassing to allow children to see that priests used to say Mass facing East, with the altar against the wall? (Let's not say anything about them wearing proper vestments, having a corpus on the cross, using altar cloths, candles, a Missal, etc. etc.)

Looking in the St Paul's Bookshop in Westminster the other day, I saw a very similar illustration in the children's Life of St John Vianney published by St Pauls. Is it too embarassing to allow children to see that priests used to say Mass facing East, with the altar against the wall? (Let's not say anything about them wearing proper vestments, having a corpus on the cross, using altar cloths, candles, a Missal, etc. etc.)If we can't be truthful with our children about the past - and this is the recent past, remember, and indeed the present too in many places - then we clearly have a problem.

Sunday, July 10, 2011

Raymond Edwards: the charge sheet

Further to my posts about Stuart Reid, Dr John Casey and Dr Raymond Edwards, I've been challenged on part of what I've said about Dr Edwards' embittered booklet 'Catholic Traditionalism', by Richard Brown, CTS' Sales and Marketing Manager. So here is a full-length treatment.

Further to my posts about Stuart Reid, Dr John Casey and Dr Raymond Edwards, I've been challenged on part of what I've said about Dr Edwards' embittered booklet 'Catholic Traditionalism', by Richard Brown, CTS' Sales and Marketing Manager. So here is a full-length treatment.In 2007 the Holy Father, in his Motu Proprio Summorum Pontificum, acting as the Church's Supreme Legislator, ruled that the Traditional Mass, and everything else contained in the 1962 Missal, Breviary, and other liturgical books of that date, had never been abrogated, and could therefore be used by any priest of the Latin Church without special permission. He explains his motivation for doing this as being twofold: to enable 'reconciliations in the heart of the Church', and because of the intrinsic value of the 'former liturgical tradition', which he summarised with the notion of 'sacrality'. It is this sacrality which has attracted so many to these traditions, he says; the resulting body of Traditional Catholics (for want of a better term) has created a pastoral situation calling for the freer availability of the Extraordinary Form; it is this sacrality which means that the Extraordinary Form should be made more freely available for the good of the whole Church.

The paragraph I have just written is obviously true: whether people like it or not, that is plainly set down in Summorum Pontificum and the accompanying Letter to Bishops. Dr Raymond Edwards, author of the CTS booklet 'Catholic Traditionalism', seems not only incapable of grasping these points but determined to obscure them and even to frustrate the Pope's intentions. That is, at bottom, what I have against this booklet.

On p3 he describes the legal status of the 1962 Missal in terms which totally cloud the important point, that it was never abrogated. He never once, in over 70 pages, concedes that the EF has value, that this value attracts people to it, and makes it worth preserving, beyond referring in passing to the value of both forms of the Mass. And as far as reconciliation goes, he throws mud at every party in the tragic conflict over the liturgy, and attributes the most base motives to every action, in a way hardly calculated to facilitate the modus vivendi which the Holy Father wishes to establish, let alone the delicate negotiations between the Vatican and the SSPX. As I have said before, if the CTS loves the Church it should withdraw this disgraceful booklet from publication. It is, in any event, now seriously out of date.

Edwards makes a number of factual errors and dubious historical claims. The Chartres pilgrimage does not take a week (p44); Vatican II does not infallibly condemn supercessionism (p61)—or anything else; the changes to the time of celebration of the Easter services were not the most important changes made to them in the 1950s (p10). Edwards' errors in his obsessively detailed history of the SSPX would be tedious to enumerate. These are not my central concern, however, which is the general spirit of this booklet.

He says, on p31, 'It is not my business here to adjudicate between competing versions of liturgical history, or offer a considered verdict on the theological points at issue.' But that is exactly what he has spent the previous 25 pages doing. His critique of Cardinal Ottaviani's objections to the prototype New Mass are superficial and patronising, and render incomprehensible the concessions (which Edwards notes) made to this critique in the revised General Instruction of the Roman Missal. But contrary to Edwards' repeated assertion, it is not this kind of critique of the 1970 Missal which first and foremost attracts people to the Church's earlier liturgical traditions, but, as the Holy Father notes, their palpable value: their beauty, their theological richness, their sacrality. To this massive fact, Edwards is willfully blind. Instead he casts around for every possible bad reason for people's attraction to the Old Mass. As well as the theological arguments which he believes he has rebutted, there is:

a 'defensive "ghetto" mentality' p27

'fondness for dressing up' p31

connection with 'hard right' and anti-semitic politics p58

In addition to these positive reasons, if one may call them that, there are the negative reasons represented by the deficiencies of the progressive party in the Church, about which Edwards had even more to say:

the 'notorious' English translation of the Missal currently in use (p21) which lacks 'accuracy and theological completeness' p22 (and is also 'woefully deficient' p37)

celebration facing the people, which Edwards assures us 'is the result of a prevalent fad, or deliberate misunderstanding' p24

'deficiencies in priests' liturgical formation' p24

'wanton destruction of liturgical furnishings' amounting to 'something akin to Mao's Cultural Revolution' p25

'seminary formation in chaos' and 'the collapse of catechesis' p25

a 'fondness for horrible fabrics and simplistic symbolism' in vestments p32

Edwards does not limit his bile to wide groups: named or identifiable individuals get it too. On the traditional side, the SSPX is tarred with every old canard about French extremism possible, a set of accusations patently irrelevant to the English speaking world. Edwards has gone to extraordinary lengths to find quotations or references which will lessen the reputations of Archbishop Lefebvre, Bishop Williamson, and even Fr Laguerie of the reconciled Institute of the Good Shepherd (p58), and the reconciled Fraternity of St Vincent Ferrer (p43). He accuses the (also reconciled) Sons of the Holy Redeemer of 'shrill polemic' (p38: particularly rich coming from him).

On the non-traditional side Archbishop Bugnini is dismissed as 'prolix' and self important (p12: again, pots and kettles come to mind), and as well as the Maoist tendencies of some Church authorities noted above we hear that 'several [bishops] in Great Britain' have imposed 'unreasonable and unnecessary conditions' on priests using the Motu Proprio (p30).

Edwards condemns the conspiracy-theory tendency of the SSPX, but indulges a fondness for such theories himself: that Levebvre was a hidden hand behind the Ottaviani Intervention (p18), that Derek Warlock was a hidden hand behind Cardinal Heenan's implementation of the liturgical reforms (p14), and that Archbishop Bugnini was sent away from Rome by shadowy, unnamed enemies (p12).

The point I wish to make is not about the truth or falsity of these claims, but about the appropriateness of this polemic and speculation in this booklet. Just at the moment when Traditionalists and their various historical opponents are having to learn to live with each other, to share churches, to cooperate in parish life and in Catholic institutions of all kinds, is this spewing of vitriol in all directions really what we need? Wouldn't it be better, as well as more historically accurate, to admit at this point that these old divisions were caused by Catholics who were sincere, intelligent, and serious, but who came to different conclusions about the needs of the time, and the implications of timeless theological and liturgical principles?

I have been taken to task for saying that Edwards says nothing about the quiet work of the Latin Mass Society within the structures of the Church. Yes, we are mentioned on p34, and in less a page and a half our existence is acknowledged. This means we get about the same space as the Sedevacantists (pp64ff). Is this proportional? Does this reflect reality, particularly in England? The SSPX gets 19 pages. The international Una Voce movement gets a single, inaccurate sentence (p35).

Edwards appears to believe that the question of the status of Judaism after the proclamation of the New Covenant is central to Traditionalism. Saying 'I have no wish to dwell on this point" (p62) he dwells there for no fewer than nine pages (60-64 and 70-75). This is an interesting question (about which Edwards has no expertise), but it has nothing to do with the attachment of Traditionalists to the Traditional Mass, and to suggest otherwise does everyone a disservice. Of the documents of Vatican II most discussed in traditional circles, Nostra Aetate (covering Judaism) would not even necessarily make the top three. These would be, I would say, Sacrosanctam Concilium, Dignitatis Humanae, and Gaudium et Spes. The latter two are not even mentioned in the booklet. It is Edwards, not Traditionalists, who has an obsession.

What is perhaps more central is the connection between the liturgical changes and the general crisis in the Church. As I have noted, it is not abstract theological considerations which, in almost all cases, attract people to the Traditional Mass, but the experience of the Mass. The importance of the liturgy for the Church is, however, affirmed strongly by Vatican II and Cardinal Ratzinger famously said that the 'collapse of the liturgy' is a prime cause of the 'crisis in the Church'. Edwards spends much energy arguing against this claim (p25 and passim). The suggestion seems to be that it is not a legitimate view for Catholics to take. But why should we, or the CTS, prefer the opinion of Raymond Edwards to that of Pope Benedict XVI? And why is he so concerned to rule out what is evidently the view of respected authorities?

Exactly the same is true of his lengthy discussion of the canonical status of the SSPX. He says he disagrees with 'some prominent clergy' (p45), later identified as including Cardinal Castrillon Hoyos, then Prefect of the Pontifical Commission Ecclesiastical Dei, which actually has oversight of the issue. Edwards thinks the Cardinal is wrong. But why should anyone care what Raymond Edwards thinks? He is not even a canonist. The booklet has become a vehicle for his personal, amateur speculations.

Overall it is perfectly clear that the CTS would never consider doing such a hatchet job on any other authorised movement within the Church. Even groups outside the Church, described in CTS booklets, could expect a more even-handed appraisal. Pope John-Paul II described the desire of some Catholics for the Old Mass as a 'legitimate aspiration': Edwards gives absolutely no acknowledgment of this legitimacy. If he hates us (and apparently everyone else) so much, why on earth was he asked to write the booklet?

- Posted using BlogPress from my iPhone