Over on Rorate Caeli I've been talking about the meaning of the statistics the LMS has collected on

Catholic marriages; there's also article on our research in the

print edition of the Catholic Herald out today, on p3. There is just so much to say about these statistics it is impossible to cover them all in a single post: here I'll say something about

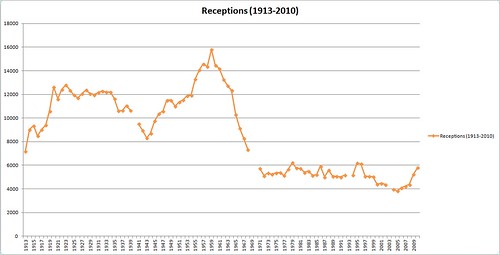

adult conversions (coyly renamed 'receptions' in the statistics for 1976 and thereafter). In another post I'll have a look at baptisms.

England and Wales has a special place in the world-wide Church, I think, as constantly refreshed by converts, to an extent far greater than in other countries. For long stretches of time Catholic life here has been dominated by converts, men like Newman and Manning in the 19th century, or Chesterton and Knox in the 20th, or indeed St Edmund Campion in penal times. One of the remarkable things about the statistics from before the Council is the scale of conversions.

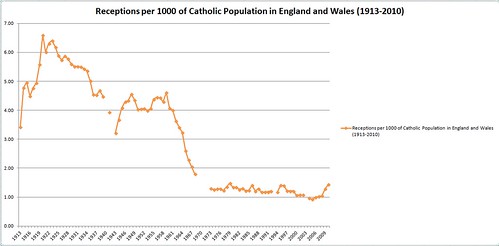

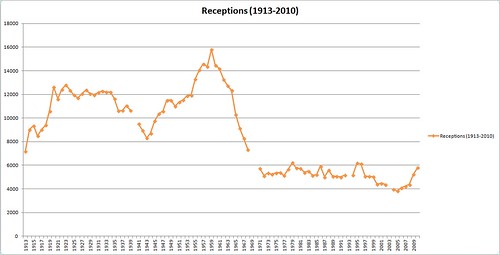

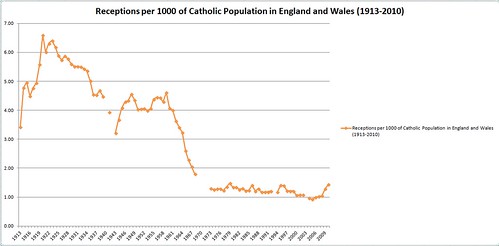

Between the start of the series, in 1912, and 1960, 534,117 people were received into the Church, not counting those received in 1942, for which data were never published (probably in the region of another 10,000). Well over half a million people. People were talking about the 'conversion of England', and it wasn't hot air. Those are the kinds of numbers which actually make a demographic impact. Remember, the

population of England and Wales was only 32.5 million at the 1931 census, and 43.8 million in 1951 (there wasn't a census in 1941.)

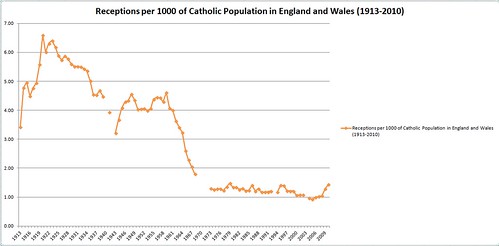

If you look at the graph expressed per 1,000 Catholics, the achievement of the interwar years is even more impressive. Fr Martindale and his like, hardly remembered today, were truly the St Francis Xaviers of their day.

However you look at it, something truly horrible happened between 1960 and 1970. The number of conversions declined by about three quarters, and assumed a plateau at this new, abysmal level. It is as if the Church shifted from one gear to another, an effect far more dramatic than the disruption caused by the Second World War.

Now, there were certain changes in the Church in the 1960s and early 70s, to say the least. They shook up the existing Catholic community, who were presumably often set in their ways. They were designed, however, to make the Church more attractive to outsiders. As Pope Paul VI wrote in

Evangelii nuntiandi (1975):

'... on this tenth anniversary of the closing of the Second Vatican Council, the objectives of which are definitively summed up in this single one: to make the Church of the twentieth century ever better fitted for proclaiming the Gospel to the people of the twentieth century.'

Well, it didn't work.

One aspect of what we see, of course, is the lessening of the phenomenon of 'marriage converts'. Catholics were no longer taught that marrying a non-Catholic was seriously problematic, and that dispensations to marry a non-Catholic were not a mere formality. Some people think this is a good thing, on the basis that any kind of incentive to become a Catholic (such as wanting marry one) undermines the purity of the motive to convert.

This is a truly silly and deeply unCatholic attitude, however. All sorts of things stimulate conversions, and are designed to do so: should we deliberately put people off the Faith, so they have to struggle more to join?

One does hear that sort of idea expressed, but it is not what the Saints did: they tried to attract the flies with honey. We should also remember the great social pressure

not to become Catholic, up to and including the 1950s. Let's hear it from the great

Fr Bryan Houghton, speaking

in persona of his fictional Bishop Forrester, but certainly from his own pre-1970 pastoral experience.

'

In the odd twenty years that I had cure of souls, either as curate or parish priest, I doubt if I ever received fewer that ten converts a year into the Church. I loved them. Along with the Eternal Truths I gave them all I had to offer. I never talked down to them, no matter how simple they were. The human mind can absorb infinitely more that it can rationalize and explain. How wonderful they were and how I admired them! ...

'I suppose rather over half, say 60%, were "marriage converts". They were often among the best. Human love seems a natural introduction to divine love. In those days, the Catholic knew he had something to give and the non-Catholic something to receive. It was right and proper that the wedding ring should be set with the Pearl of Great Price. And the heroism of so many of those marriage converts! Not only were they cut off from their families (a more tragic situation in the working than in the educated classes), but they undertook willingly to obey the marriage laws. "I am only a marriage convert, Father"; my dear, you could be nothing more noble.'

(

Mitre and Crook (1979) pp85-6)

Most of Fr Houghton's experience was garnered as Parish Priest of Bury St Edmunds in East Anglia (from 1955 to 1970), a part of England with an exceptionally low number of Catholics. There, one might assume, there would be more Catholics marrying non-Catholics, or converts, than in places of higher Catholic density, such as Lancashire or the Irish community in London. Supposing, then, not 60% but half of all conversions in England and Wales over this period were 'marriage converts', that would mean a bride or groom had converted in about a quarter of the weddings taking place over the period 1913-1960, a figure which is striking but not totally implausible.

Suppose, then, we halve the number of conversions recorded in 1959, and compare this reduced figure with the total for 1973 (after the gap in the series of Directories): what then? Well, then we get a decline of 27%. In other words, even if we took the insane view that, because of marriage converts not being sincere, the pre-1960 figures are inflated by 100%, we are still looking at a huge decline in conversions.

Has the new policy of granting dispensations to marry non-Catholics without quibble, and of not encouraging young people to seek partners from the household of the Faith, been a roaring success? I don't have numbers for divorces and annulments, but I think it is pretty obvious that this policy has been a disaster. The 'pastoral' policy, as so often, has created a pastoral nightmare.